Decoration Day, Memorial Day, and the Family Reunion

Decorating the graves of the Civil War dead

By Bobbi Spiker-Conley

Our family’s tradition of gathering each May at the Spiker Farm is rooted in the commemoration of those who died in the Civil War. On both sides of that conflict, families and brothers-in-arms of the fallen, honored the heroes by laying flowers on their graves. This day of remembrance was initially known as Decoration Day.

Even before the war, many rural West Virginia communities and churches came together in late Spring or early Summer to clean up their local cemeteries. The grass was cut, fences were weeded, gravestones were leveled and cleared of debris. Then a single day was set aside for decorating the graves with fresh flowers and small tokens. Decoration Day balanced reflection and celebration through respectful graveside prayers, the sharing of stories, singing, and often a communal “dinner on the grounds.”

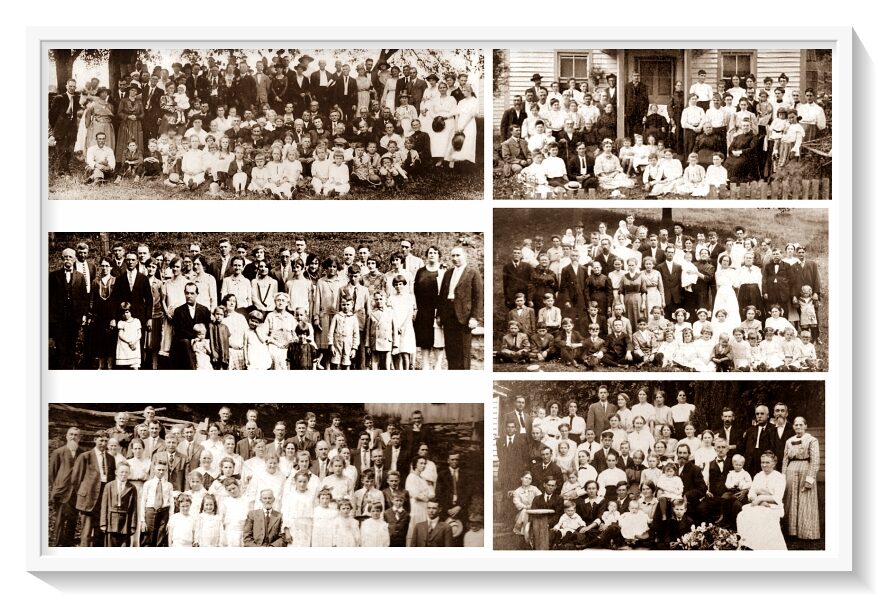

The Zinn homestead (what we now call the Spiker Farm,) was centrally located among several cemeteries that our ancestors visited on Decoration Day. Likely for that reason, the farm quickly became an annual homecoming site for those that had moved out of the area. Friends would gather at the farm in early morning, disperse in small groups to the various cemeteries, then return to the homestead for an afternoon of music, games, and food. Various branches of our family tree came together at predetermined locations each year to pose for “the annual family reunion photo.”

West Virginia wasn’t the only state to observe the customs of Decoration Day. American writer and author, Mrs. Mary Simmerson Cunningham Logan, wrote of witnessing “the devotion of the people of the South to their heroes.”

She was one in a group that toured battlefields of Virginia in the spring of 1868. “…No one who has never made the pilgrimage that was my log can conceive of the desolation of that country immediately after the war,” she wrote in The Los Angeles Times. “The ruin seemed complete. We found it well-nigh impossible to get any sort of conveyances from points on the railroads to the battlefields, and those men who were acquainted with the country and the history of the various battles were all too busily engaged in repairing their fallen fortunes to spare the time to guide us. Yet there was no spirit of enmity in their disinclination to help us, but merely the pitiful tale of war’s disasters and the necessity for constant toil to rebuild the waste caused by four years of bitter strife. We finally, however, managed to get wagons of one sort and another from place to place as we journeyed and an occasional guide who had participated in the battles whose sites we were visiting. It was probably the most interesting experience in all my life, yet one which I should not care to repeat, for not until then had I known the true purport of war.

“…We were in Petersburg, Virginia, and had taken advantage of the fact to inspect the oldest church there, the bricks of which had been brought from England. There was an old English air all about the venerable structure, and we passed to the building through a churchyard. The weather was balmy and spring-like, and as we passed through the rows of graves, I noticed that many of them had been strewn with beautiful blossoms and decorated with small flags of the dead Confederacy. The sentimental idea so enwrapped me that I inspected them more closely and discovered that they were, every one of the graves, of soldiers who had died for the Southern cause. The action seemed to me to be a beautiful tribute to the soldier martyrs and grew upon me while I was returning to Washington. [My husband,] Gen. [John] Logan was at that time the Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, with his headquarters in Washington, and as soon as he met me at the station I told him of the graves of the Southern soldiers in the cemetery at Petersburg. He listened with great interest and then said: ‘What a splendid thought! We will have it done all over the country, and the Grand Army shall do it! I will issue the order at once for a national Memorial Day for the decoration of the graves of all those noble fellows who died for their country.’

“He immediately entered into a conference with his several aides, with a view of selecting a date that should be kept from year to year. He realized that it must be at a time when the whole country was blooming with flowers, and May 30th was finally selected as the best season for the annual observance of the day. It was not too late for the warmer States or too early for the cooler ones. The order that finally emanated from headquarters was, in part, as follows:”

Headquarters Grand Army of the Republic, Adjutant General’s Office, 446 Fourteenth street, Washington, D.C.,

May 5, 1868

General orders No. 11

The 30th of May, 1868, is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of the comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village and hamlet churchyard in the land.

…We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance. All that the consecrated wealth and taste of the nation can add to their adornment and security is but a fitting tribute to the memory of her slain defenders. Let no wanton foot tread rudely on such hallowed grounds. Let pleasant paths invite the coming and going of reverent visitors and fond mourners. Let no vandalism of avarice or neglect, no ravages of time testify to the present or to the coming generations that we have forgotten as a people the cost of a free and undivided public.

If other eyes grow dull, other hands slack and other hearts cold in the solemn trust, ours shall keep it well as long as the light and warmth of life remain to us. Let us, then, at the time appointed gather around their sacred remains and garland the passionless mounds above them with the choicest flowers of springtime; let us raise above them the dear old flag; let us in this solemn presence renew our pledges to aid and assist those whom they have left among us as sacred charge upon the nation’s gratitude, the soldier’s and sailor’s widow and orphan.

It is the purpose of the Commander-in-Chief to inaugurate this observance with the hope that it will be kept up from year to year while a survivor of the war remains to honor the memory of his departed comrades…“

By order of

John A. Logan

Commander-in-Chief.

N. P. Chipman,

Adjutant-General.

By his order, Decoration Day became a nationwide day of remembrance for the more than 620,000 soldiers killed in the recently ended war.

That first year, more than 27 states held some sort of ceremony. By 1890, every former state of the Union had adopted it as an official holiday. (Southern commemorations often differed by state and dates — a tradition that continues today: Nine southern states officially recognize a Confederate Memorial day, with events held on Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ birthday, the day on which General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was killed, or to commemorate other symbolic events.)

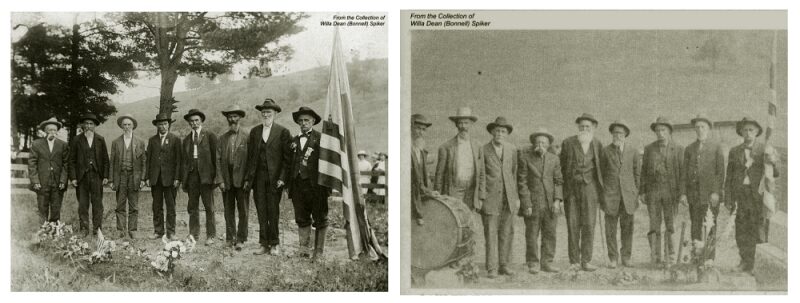

The ”Old Soldiers” from our hometowns formed local veterans’ associations that promoted social events like the Decoration/Memorial Day commemorations. (See photos.) Later, these ceremonies hosted by the Union and Confederate veterans themselves, were continued by tradition and community spirit.

Over the years, the meaning of Decoration Day evolved, gradually expanding from a commemoration of Civil War dead, into a day to honor fallen members of theAmerican armed forces from all wars. And just as the meaning evolved, so did the name. By the late 19th century, many Americans were using the term Memorial Day.

For decades, Memorial Day continued to be observed on May 30th — regardless what day of the week that may be — but in 1968, Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act (legislation declaring certain holidays would take place on certain Mondays in order to create a three-day weekend for the nation’s workers) which established Memorial Day as the last Monday in May. The change went into effect in 1971.

In our early childhood, we kids simply called it ”May 30th.” It was an important date to remember because it signaled our first “official” day of summer break, ensured a visit to the Spiker farm was inevitable, and it meant we were finally permitted to go barefooted outside!!! Sheltered from the news headlines, we knew nothing of Congress or of changing dates. It wasn’t until we were older that we realized a switch must have happened when we weren’t paying attention.

On the other hand, our father made certain we paid attention to the respectful customs of (what he always called) Decoration Day.

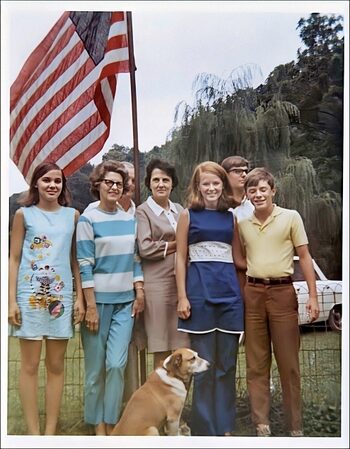

Like previous generations, family and friends gathered at the Spiker farm on the Sunday closest to May 30th. In early morning, Uncle Brad walked to the flagpole located in the front yard and silently attached his American flag. He raised the flag to the peak then slowly lowered it to half-staff. My father explained to me that this gesture was to mourn those who died in service to our country.

Most of us attended the morning services at the South Fork Baptist Church and lingered afterward to pay our respects to those buried in the churchyard cemetery. Returning to the farm, Uncle Brad stopped at the flagpole where, at noon, he briskly hoisted the flag to the peak again. There it remained until sunset in honor to the living military personnel.

My father revealed that many of our ancestors served in the Civil War, including our second great-grandfather, Jacob Bradford, who died from wounds he’d received in battle. His memorial was one of those our family decorated at the Indian Creek Baptist Cemetery in nearby Washburn. (We will tell more of his story in the July 2020 edition of the Spiker Gazette.)

Rural cemeteries like these rely on private contributions of money and labor to maintain the properties and burial sites. Jake, Gay and their children performed much of the upkeep by hand. (As seen here.) As they aged and became less able to physically perform some of the more arduous tasks, they contributed financially to the South Fork church and cemetery.

In March 2012, Mike Spiker, Mark Spiker and Miles Ball formed a three-member Board to establish the “South Fork Cemetery Association.”

This 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization assists in the long-term care and maintenance of the cemetery where so many of our ancestors are buried. As Mike reminded us, “These old cemeteries are hard to keep up, and if the church ever ceases to operate, then at least there will be something in place to cover mowing the grass and other maintenance at the cemetery.”

Ordinarily, contributions (both private and as proceeds from the family Reunion Auction) are donated to the Association during the annual Spiker Family Reunion. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the reunion has been postponed (and most likely cancelled until next year.) This means that critical funding may not be collected as expected. If you are in a position to donate this year, please make your tax-deductible payment to:

South Fork Cemetery Association

6508 Grove Summers Rd.

West Union, WV 26456

To paraphrase General Logan’s Order:

Let no neglect or ravages of time testify to the present, or to the coming generations, that we have forgotten the cost of a free and undivided public. If other eyes grow dull, other hands slack, and other hearts cold in the solemn trust, ours shall keep it well as long as the light and warmth of life remain to us.